Dying for a Living - The Most Dangerous Jobs of the 19th Century for Children

C.A. Asbrey

The average life expectancy in the mid 19th century was forty for men and 42 years for females. That was an average, though. There are many people who lived to a ripe old age. For instance, Margaret Ann Neve was born in 1792, three months before Marie Antoinette was executed, and while George Washington was president of the United States. She died in 1903, a month before her 111th birthday. She spoke of visiting the battlefield at Waterloo during 'Napoleon's troubled times' whilst on her honeymoon. Clearly, the idea of a romantic day out has changed over the years, but she did find the belt buckle of an Imperial Guard as a keepsake. But Neve was wealthy. She was a friend of Queen Victoria, and enjoyed a good diet, lifestyle, and the best medical care. The poor were not so fortunate. By 1900 the average life expectancy had risen to only forty five for men and 50 for women.

|

| Margaret Ann Neve |

One of the major problems was the danger from infections, either from minor injuries, or from childbirth. Another was the total lack of consideration for health and safety for people in the workplace. Children were not excepted from the harsh realities of work life either. Poor children were a burden, the least powerful, and unrepresented by any group. Homes couldn't wait to get rid of them, shifting responsibility for them to whoever took them on. The authorities cared little about their welfare, and even less about the working conditions they faced when taken on for gainful employment.

At the bottom of the list were those who rummaged through waste and garbage for anything recyclable. Remarkably little was wasted in the 19th century. Old cloth, bone, blood, urine, even animal waste; all had a value and would be sold on to make glue, fertilisers, paper, and in the use of tanning, dye making, or even in production of gunpowder. The housewife would scan the garbage bin to prevent servants being too wasteful, and wagons toured the streets looking for waste to purchase. Even ashes had a value. They were used in gritting paths in icy periods, any small bits of wood or coal were re-burned, and wood ashes were used as fertilizer. Bones were boiled until bleached white to make stock, and then sold on. Pig bins were common, and scraps were converted to pigswill or chicken food.

|

| Mudlarks of London |

What was left, was scavenged by children for any scraps worth using. Some children in London even paid to be allowed to scavenge below the waterline on the tidal Thames. They were called the mudlarks, and they not only could find flotsam and jetsam from the shipping, but they could hit lucky and find historic coins or valuables lost from bridges. If they were unlucky, they could get injured or get cut off by the ruthless tides and drown. They routinely found bodies; both human and animal.

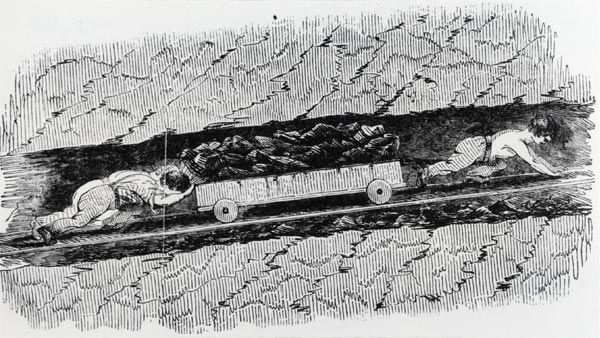

Children were popular in any role which required squeezing into small spaces. Rat catchers would take children from workhouses and orphanages in much the same way as chimney sweeps would. These children would be used to go into sewers and tiny holes as rats were valued if caught alive, as they were used in sports (a dog would be put in a pit with a large number of rats, and bets would be taken on how long it took for the dog to kill them all. The children risked bites, disease, infection, and the inevitable danger of being jammed in a hole where they would suffocate in the dark. Their counterparts in the chimney sweeping world could suffer a similar fate. Children of both genders were sent up chimneys, some no more than nine inches in diameter. The worst thing to happen would be a slip. If they didn't fall all the way to the bottom and fracture bones, they could get themselves caught with their knees jammed up at their chests. That would restrict their breathing until they slowly smothered. Sometimes bricks had to be removed from the chimney to remove the child's body. If they survived to enjoy a career, they were prone to a squamous-cell carcinoma which was caused by soot particles irritating the skin, particularly on the scrotum.

Mule spinners were children who scampered beneath the huge mechanical looms to collect scraps of cotton and clear jams. The machines spun

cotton into thread and never stopped. Children crawled underneath enormous moving machines. There was barely room to raise their heads. There was no way of stopping them if something went wrong. It was dangerous work. Many lost children lost fingers, limbs, or were even crushed to death. If they were lucky enough to get too big for the role, they could move up the ladder within the mills. However, deafness was common due to the constant incessant noise, and Byssinosis, a lung disease caused by inhaling cotton fibres brought an early and unpleasant death.

I'm sure many of you will have heard the tale of The Little Match Girl, but making the matches was far more dangerous than trying to sell them. Phossy Jaw or more accurately, phosphorus necrosis of the jaw, caused the bones in the jaw to rot away. Most of those working with white phosphorous were young girls, and they were forced to work without protection, and even ate at their workstations. Working conditions were terrible, with frequent beatings, and a culture of abuse. Things got so mad that the match girls went on strike in London in 1888 for better working conditions, including demanding that the companies use safer red phosphorus instead of white. It difficult to overstate how powerless and poor these girls were. They lived hand to mouth, and were one step from living on the streets. The fact that they went on strike is a measure of how desperate they were. They were destined for a horrible slow death, so had nothing to lose. They had to try to make their own futures safer.

Children involved in glass making faced serious injuries and potential death every day. “Dog boys” or “blower’s dogs”—so-called because they were trained to follow the adult glass blower’s whistle—these boys handled and cleaned every piece of molten glass that the glass blower took from the furnace. They repeated this process hundreds of times in a single shift. As glassblowers were paid on piecework, they kept up a rapid pace, forcing the children working with red hot glass as speed to try to keep up. It was a recipe for disaster. Boys were blinded by bits of flying glass, and glass dust, known as 'blow-overs', caused excruciating pain if it got into the lungs or the eyes. Apart from the obvious burns, the boys often caught pneumonia in the winter, caused by the drastic temperature change from walking home after a day in front of a huge furnace.

Legislation eventually changed conditions for children in the developed world. As well see in the next blog post, life often didn't get much better when they grew up.

In All Innocence

Excerpt

Almost everyone woke simultaneously, jolted by the sound of the brakes grinding, and the engine puffing and huffing in protest at an unscheduled stop. Jake’s hand reached for his gun even before he was fully conscious.

“No!” The cry came from Jeffrey, the younger steward, who staggered into the aisle in shock.

Nat strode out of the curtained area, fastening his trousers. “What’s wrong?”

“Mrs. Hunter,” Jeffrey stammered. “She’s dead.”

Nat dragged the curtain aside, revealing the tiny-framed woman lying in a pool of blood. He kneeled and scrutinized her. “Bring a lamp.” He reached out and touched her face. “She’s alive. She’s warm. Fetch Philpot. He’s a doctor.”

The Englishman wandered groggily forward. “I’m not a doctor. I’m a—”

“We don’t care what you are, Philpot,” Jake growled. “You’re the nearest thing we’ve got. You’ve got medical training. Get in there.”

Mrs. Hunter’s eyes flickered weakly open. “My moonstone. Miss Davies—she took it.” She fell back into insensibility.

Jake frowned and his keen blue eyes looked up and down the railway car at the passengers crowded in the aisle in various stages of undress. “Where is Miss Davies? Have you seen her, Abi? You’re bunkin’ with her.”

“No, she isn’t here.” Abigail frowned. “I haven’t seen her for ages. She wasn’t even in her bunk when I changed Ava.”

Malachi padded briskly up to the group, pushing various butlers out of his way as they milled around. “Oh, my goodness! The poor woman.”

Jake nodded. “Yeah, Philpot’s seein’ to her. She’s still alive. Why’ve we stopped? We ain’t at a station.”

Malachi quickly fastened a stray button. “I’m sorry, gentlemen. I have been informed that a rock fall has blocked the tracks. We will dig it out and be on our way as soon as possible.”

“A rock fall? So, how far to a station?” Nat asked. “We’re high in the mountains, miles from anywhere.”

There was another ominous rumble somewhere above them and the carriage shook. The roof thundered with the thumps and clattering of stones and gravel pounding the roof. Worried glances rose upward while Abigail hunched protectively over her baby. The noise gradually stopped, but for an occasional patter of settling gravel and stones shifting above them.

The head steward’s brow crinkled into a myriad of furrows. “I’d best go and check that out.”

Nat’s brows knotted into a frown. “We’re miles from anywhere? So where has Maud Davies gone?”

“No!” The cry came from Jeffrey, the younger steward, who staggered into the aisle in shock.

Nat strode out of the curtained area, fastening his trousers. “What’s wrong?”

“Mrs. Hunter,” Jeffrey stammered. “She’s dead.”

Nat dragged the curtain aside, revealing the tiny-framed woman lying in a pool of blood. He kneeled and scrutinized her. “Bring a lamp.” He reached out and touched her face. “She’s alive. She’s warm. Fetch Philpot. He’s a doctor.”

The Englishman wandered groggily forward. “I’m not a doctor. I’m a—”

“We don’t care what you are, Philpot,” Jake growled. “You’re the nearest thing we’ve got. You’ve got medical training. Get in there.”

Mrs. Hunter’s eyes flickered weakly open. “My moonstone. Miss Davies—she took it.” She fell back into insensibility.

Jake frowned and his keen blue eyes looked up and down the railway car at the passengers crowded in the aisle in various stages of undress. “Where is Miss Davies? Have you seen her, Abi? You’re bunkin’ with her.”

“No, she isn’t here.” Abigail frowned. “I haven’t seen her for ages. She wasn’t even in her bunk when I changed Ava.”

Malachi padded briskly up to the group, pushing various butlers out of his way as they milled around. “Oh, my goodness! The poor woman.”

Jake nodded. “Yeah, Philpot’s seein’ to her. She’s still alive. Why’ve we stopped? We ain’t at a station.”

Malachi quickly fastened a stray button. “I’m sorry, gentlemen. I have been informed that a rock fall has blocked the tracks. We will dig it out and be on our way as soon as possible.”

“A rock fall? So, how far to a station?” Nat asked. “We’re high in the mountains, miles from anywhere.”

There was another ominous rumble somewhere above them and the carriage shook. The roof thundered with the thumps and clattering of stones and gravel pounding the roof. Worried glances rose upward while Abigail hunched protectively over her baby. The noise gradually stopped, but for an occasional patter of settling gravel and stones shifting above them.

The head steward’s brow crinkled into a myriad of furrows. “I’d best go and check that out.”

Nat’s brows knotted into a frown. “We’re miles from anywhere? So where has Maud Davies gone?”

“With the moonstone?” Jake strode over to the door and looked out at the huge feathery flakes drifting down from the heavy skies onto an expansive mountainous vista. “There’s nowhere to go.”

Chilling, how casual people in power can be, partic in out of sight, out of mind jobs.

ReplyDeleteIntriguing and exciting excerpt!

I so agree. Life was so cheap, and people felt exactly the same pain and anguish as we do now. Thanks Lindsay.

DeleteReading Charles Dickens' stories in my teens opened my eyes to the social and cultural part of history involving child labor. Intellectually, I understand the horrors poor children endured to simply survive. Emotionally, I can't fathom it. I'm looking forward to reading your next article.

ReplyDeleteThank you Kaye. Yes, this stuff was the very essence of Dickens' social activism. He was poor as a child and did some pretty horrible work himself.

DeleteMost informative. I was aware of some of the jobs children did, but you added many more to the list. It is sad to think 'progress' was made on the backs of the less fortunate. Doris

ReplyDeleteThanks, and I'm sure I missed many more too. Life was very cruel in the past.

DeleteCompared to the lives of children in your post our kids today seem like spoiled, over-protected, little hellions to these abused and uncared for children. I was horrified by the jobs kids were forced to do. Didn't their parents care about them either? It was an unimaginable horror show back then. I cannot get that manure dust out of my head. This was quite an eye-opening article, Christine.

ReplyDeleteLoved your excerpt from IN ALL INNOCENSE. Right off there's a dead body!

All the best to you, Christine!

Thank you, Sarah. There were good and bad parents, just like there are today, but there was nothing between them and starvation. Starving women turned to prostitution too, and that just compounded their problems. Some of the children were unwanted pregnancies, some were much-loved. Life was horrible for the very poor and they had almost nothing in the way of options. The reason many emigrated to the New World is because carving out a life there was no harder than the life they left behind, but offered a chance for to work for themselves instead of others.

DeleteThis comment has been removed by the author.

ReplyDeleteIt breaks my heart to think what dangers these children suffered to survive and in some parts of the world horrible conditions still prevail for children today. It is just so wrong and so unfair. If this information could be part of a school's social studies curriculum, then perhaps the spoiled kids who balk at simple household chores would have a better appreciation of their living conditions. We just have to turn on the tv and see how some children are still sifting through garbage to survive. Sadly, human nature doesn't change--just the window dressing is changed. As usual, Christine, you provide a thought-provoking blog and excellent excerpt from your books.

ReplyDeleteThank you so much, Elizabeth. Yes, so many people led hard and difficult lives. It would be sad to forget them.

DeleteSorry I missed reading this one earlier. An important piece of history that it is crucial we don't forget.

ReplyDeleteDefinitely, life was so cheap and we must never let it happen again.

Delete