In an age without freezers and only limited storage methods – smoking, salting, drying, preserving, keeping – all foodstuffs had to be produced in time to the rhythms of the farming year. In the Middle Ages, that meant the Christian calendar. Feasts were allied to the high points of harvests, saints’ days, Christ’s life, the change of the seasons and the winter and summer solstices.

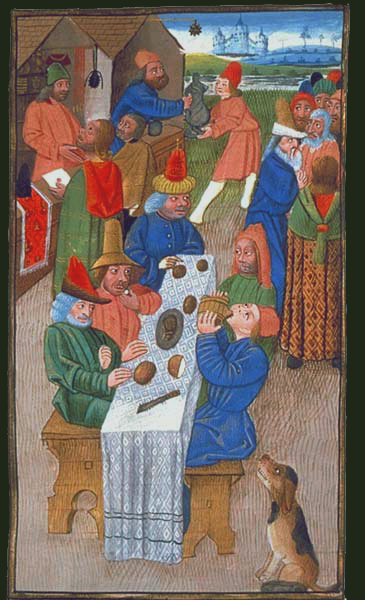

Christmas especially, covering the darkest time of the year and preceded by the fast of Advent, was celebrated for almost two weeks by all classes. No work was done in that ‘quiet’ season of the farming year and people celebrated by dancing, singing, story-telling, drinking and eating.

In the countryside, some lucky peasants might be fed within their lords’ manor houses over Christmas as part of the Christian tradition of charity and share in rich dishes and strong beers. Other peasants would feast at home. Meat, as a luxury, would certainly be enjoyed, usually in the form of bacon, salted beef or mutton. Such cuts would be made into stews or slow roasted. Pepper was used as a spice by all classes and at Christmas carefully hoarded spices such as ginger, some dried herbs from the kitchen garden and perhaps even exotic fruits such as dried raisins might be added to the stews to add different flavours. We know that peasants had access to exotic spices and dried fruits because the Sumptuary Laws forbade indulgence in both rich clothes and expensive foods by the ‘lower’ classes.

Fine wheat bread, if peasants could produce it (by grinding the flour in secret away from their lords’ mill) would be a treat. River fish or eels would make a change from the usual salted dried cod of winter-time. Waterfowl, chickens, and – once they had escaped and bred from their specially constructed warrens – rabbits, could be caught, roasted or turned into stews and pies.

Hard cheese, which would keep through the winter, might have been part of a peasant’s Christmas feasting and certainly there would have been pottages, vegetable one pot stews made from the cut and come again greens and root vegetables (not potatoes yet) from the kitchen garden.

As well as food treats, peasant households would decorate their homes for their Christmas feasts. Holly, ivy and mistletoe were cut and brought indoors to make the Christmas Bush that hung from the rafters. And after Christmas there was the festival of wassailing in cider apple districts. People would gather in the orchards and light fires under the trees, dance round them and drink to them.

As well as food treats, peasant households would decorate their homes for their Christmas feasts. Holly, ivy and mistletoe were cut and brought indoors to make the Christmas Bush that hung from the rafters. And after Christmas there was the festival of wassailing in cider apple districts. People would gather in the orchards and light fires under the trees, dance round them and drink to them.Richer peasants might feast on lamb or suckling pig, served with the first spring greens. Eggs featured heavily since they symbolised the stone rolled away from the tomb of Christ. Pace or paschal eggs, coloured with onion skins and wine, were part of the Easter feast, which, like Christmas, could last over several days.

What did people drink during these festive times?

A drink common to ancient Roman and northern European lands was mead, made of honey and water. Mead was the drink of choice at Anglo-Saxon feasts. Because drinking water was so often impure in the ancient world, ale was the 'everyday' drink, but mead was for feasting. There were mead halls and, in the halls, mead benches, where men sat drinking side by side. Drinking horns and glasses were richly ornamented and highly prized. Anglo-Saxon wine, some grown from grapes that could flourish in the south of England, was light, quickly consumed and not very strong. Ale, drunk by all ages, was a sweetish, thick drink, again not very alcoholic. Mead was the intoxicating draft, subject of riddles and poetry and drunk prodigiously in seasonal feasts. A later recipe from the fourteenth century describes ‘fine mead’, with the honey pressed from the combs and added to water left after boiling the empty combs (as for ordinary mead), then flavoured with pepper, cloves and apples and left to stand.

A drink common to ancient Roman and northern European lands was mead, made of honey and water. Mead was the drink of choice at Anglo-Saxon feasts. Because drinking water was so often impure in the ancient world, ale was the 'everyday' drink, but mead was for feasting. There were mead halls and, in the halls, mead benches, where men sat drinking side by side. Drinking horns and glasses were richly ornamented and highly prized. Anglo-Saxon wine, some grown from grapes that could flourish in the south of England, was light, quickly consumed and not very strong. Ale, drunk by all ages, was a sweetish, thick drink, again not very alcoholic. Mead was the intoxicating draft, subject of riddles and poetry and drunk prodigiously in seasonal feasts. A later recipe from the fourteenth century describes ‘fine mead’, with the honey pressed from the combs and added to water left after boiling the empty combs (as for ordinary mead), then flavoured with pepper, cloves and apples and left to stand.

Happy Holidays!

(All pictures from Wikimedia Commons).

Lindsay Townsend

I mention Christmas feasts in "Sir Conrad and the Christmas Treasure" and "The Snow Bride", plus the lack of festing in "Sir Baldwin and the Christmas Ghosts". You can find these romances on Amazon and at the Prairie Rose Website here

After reading this informative article I see that medieval English peasants had a great deal of fun and good eats during the holidays. So much is written about the hardships of the peasants I was glad to read about their festivities and pleasures. This was a delightful holiday piece and I enjoyed it very much.

ReplyDeleteI wish you a most happy Christmas, Lindsay.

And happy holidays and season's greetings to you, Sarah!

ReplyDeleteI wanted to focus on the less-well off in this piece, since we tend to hear so much about the feasts of the nobility.

Great to see the peasants getting a mention, instead of all the aristocracy. The mundane parts of history are the parts that interest me most. I love seeing how people really lived and celebrated. Thanks for this post and Merry Christmas.

ReplyDeleteIt is the common folk who are so fascinating and their story as told by you is fascinating. Thank you. Doris

ReplyDelete