Louise

Amelia Knapp Clappe

(née Smith) was born on

July 28, 1819 in New Jersey. She spent most of her youth and young adult life

in Massachusetts. Her father Moses Smith, graduated from Williams College in

Massachusetts in the year of 1811, and he once had the responsibility of being

in charge of a local academy. Both Moses and his wife came from Amherst,

Massachusetts. There is some speculation that her parents might have been

cousins, for both Moses' mother and wife shared the same maiden name (Lee).

Both of Louise's parents died before she turned 20, with her father dying in

1832 and her mother in 1837.

Louise

was one of seven children, with three brothers and three other sisters. In 1838

she attended a female seminary in Charlestown, Massachusetts. The following two

years she continued her education at Amherst Academy. She was a good student,

whose interests included metaphysics. Following in her father's footsteps, Louise

also got involved with education, teaching in Amherst in 1840.

Around

the same time, she was introduced to Alexander Hill Everett who happened to be

at least twice of Louise's age. Everett was a distinguished author, and Louise’s

relationship with him was mostly an intellectual one. Between the years 1839 to

1847 they had exchanged forty-six letters. During this time Louise also met her

future husband, Fayette Clappe. When Louise told Everett about her new relationship,

he was not pleased and things ended poorly.

Born in June 1824 in Chesterfield,

Massachusetts, Fayette Clappe was five years younger than Louise. Fayette's

family also had a different spelling of Clappe, and instead spelled it as

Clapp. He started his college education at Princeton, but finished up at Brown

University, graduating in 1848. He briefly continued his education, studying

medicine at Castleton in Vermont. Similar to Louise's mother, Fayette's mother

also bore the maiden name Lee. The exact date of their wedding is unknown;

however, some believe it occurred in either 1848 or 1849. Louise and Fayette

never had any children together.

Louise had always wanted to go to

the West, first mentioning her desire to do so in one of her letters to

Everett. While Fayette was studying medicine in Vermont, the couple caught gold

rush fever. Louise

and Fayette later moved out West to California where she took on the pen name

of Dame Shirley and wrote her widely known Dame Shirley letters.

Upon arrival in California, both

Louise and Fayette were ill. Louise had suffered from chronic illnesses

throughout the 1830s and 1840s. Her first year in California living in San

Francisco and Plumas (near Marysville) was spent taking care of Fayette who had

been sick for their whole first year. During this time, Fayette was able to

obtain an absentee degree from Castleton, making him a doctor. He was elected

as a delegate to a political nominating convention and was also chosen to serve

on a committee protesting the tactics of agents hired to help the incoming

immigrant wagon trains from across the Plains.

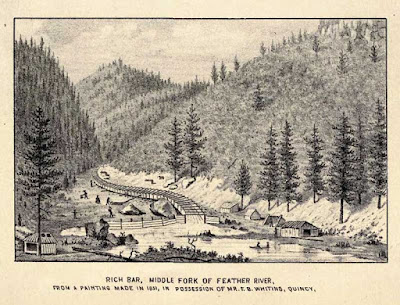

Known as “Dame Shirley,” she famously

captured the spirit of California Gold

Rush society in a series of 23 letters to her sister in the East.

Adopting for these the persona of a self-consciously whimsical “Dame Shirley,”

she wrote the Shirley Letters in 1851 and 1852 from the gold mines at

Rich Bar and Indian Bar on the Feather River, where she had ventured in company

with her physician husband. In these

letters she wrote of life in San Francisco and the Feather River mining

communities. She focuses on the experiences of women and children, the perils

of miners' work, crime and punishment, and relations with native Hispanic

residents and Native Americans.

Throughout the years there have been

multiple editions of her letters in print. Her letters have been described as

being both witty and disturbing, while giving insight into California mining

life.

In her earlier letters, Shirley

never uses a full name and instead uses just a first initial. The Shirley

letters were all carefully written, and they showed off Louise's education and

writing skills, for all of the letters were unique and extremely rich in

detail. In the sixth letter written back to her sister Molly, Shirley discusses

her shock at how vulgar the men in California are, and the wider tolerance for

such vulgarity. The

same letter also indicates that her marriage with Fayette was failing,

describing his business transactions with some bitterness. In her twelfth

letter, Louise claims that she wants to give the true picture of mining life,

and she did so from a distinctly female perspective. Some later authors and

publishers believe her letters were never meant to be made public at the time

she wrote them; others believe that was her intent all along.

Her marriage with Clapp started to

falter around 1852. While the two separated around that time and Fayette headed

back East, their marriage did not officially end until some years later.

While Louise was staying in San

Francisco, she made the acquaintance of Ferdinand C. Ewer, who printed her

Shirley letters in his new periodical, "The Pioneer" in 1854-1855. Her

writings influenced the later writing of gold rush chronicler Bret Harte.

Not only did Louise submit her

letters, but she also wrote two other articles for the Pioneer. The two

articles "Superstition" and "Equality of the Sexes" once

again did not show off her writing gifts. In both articles she still identifies

herself as Mrs. Louisa Clapp, even thought she and Fayette had split at this

point.

|

| Photo ctsy of The Philadelphia Rare Books and Manuscripts Company https://www.prbm.com/FeaturedBooks/_Clappe_Archive.php |

Louise later wrote for the Marysville

Herald in the spring and summer of 1857. The Herald was not much of a

newspaper, but more of a vehicle for advertisements.

Louise

began teaching in San Francisco in 1854. In 1856 she officially filed for

divorce from Fayette. While living in San Francisco, she was well liked and

became well known for her teaching and writing. She taught for two different

all-girls schools, Denman Grammar School, and Broadway Grammar school. She also

taught well-attended

evening classes in both art and literature. In 1857 she most likely made nine-hundred

dollars for the year. Between 1868 and 1869 she switched the spelling of her

last name to Clappe. Throughout the next decade she went back and forth between

the two different spellings.

While in

San Francisco, she adopted and raised a niece, Genevieve Stebbins. In 1878 she

retired from teaching. The Denman School raised a farewell gift of two thousand

dollars. Louise lived out the remains of her life in New York City for the next

twenty eight years. She resumed her writing in 1881 when a periodical at

Hellmuth Ladies' College at London, Ontario published a series of her articles

under her Shirley name.

She

returned to her native New Jersey in 1878. She lived on to the age of 87 and

died from chronic diarrhea and senility on 11 February 1906. Her headstone

reads that she was the wife of Dr. Fayette Clappe.

Sources:

Wikipedia

Google Books; The Shirley

Letters from California Mines in 1851-52: Being a Series of Twenty-three

Letters from Dame Shirley (Mtrs. Louise Amelia Knapp Smith Clappe) to Her

Sister in Massachusetts and Now Reprinted from the Pioneer Magazine of 1854-55,

with Synopses of the Letters, a Foreword, and Many Typographical and Other

Corrections and Emendations by Thomas C. Russell; Together with "An Appreciation"

by Mrs. M. V. T. Lawrence

Starting in January, 1884, Big Meadows Valentine, is the first book in the Eastern Sierra Brides 1884 series. If you want to know why only chickens will win Beth's heart, be sure to get your copy from Amazon. CLICK HERE.

These early women writers are so interesting. Many traveled and made use of that fact in telling their stories. Thank you for adding to the list. Doris

ReplyDeleteThank you, Doris. I was searching for information on mining practices hoping to put together something not too dry. I came across her name, and it went from there. I've read Bret Hart's Luck of Roaring Camp, but had no idea he got the idea from her writings.

DeleteI find the question of whether she intended to publish the letters or not interesting. So often what get saved from the past is more luck than intent. Either way, I really enjoyed your blog. Fascinating.

ReplyDeleteI found it interesting, too. Louise must have kept a copy of her letters. I don't recall reading that she went back east where she could have gotten them from her sister, nor was mail very reliable between California and the East back in the 1850's. She may have kept a copy in case her sister didn't receive one of the letters, then later came up with the idea to publish them...especially after she separated from her husband and needed a source of income. Thanks for your comment.

DeleteThis is so interesting. I love these gems of 'colorful backstories'. I wonder what these women who wrote about their westward adventures would think about how drawn to these accounts the writers of 100+ years later are. (she wrote ungrammatically - lol)

ReplyDeleteDame Shirley is a fabulous pen name.

I know, huh? Everything was much slower back then. Think about it -- most readers used to expect a huge novel 80K+ words. Now, to some readers they would seem too slow and wordy because there are so many novella length works available. Times change.

DeleteI felt bad for her that she and her husband did not have a successful marriage.

ReplyDeleteThose letters to Everett must have been very interesting considering he must have felt they had a love connection.

One thing is for certain, she had an adventurous life. I know she must have had fun writing the Shirley Letters.

A lovely accounting of her life, Keena.