From the time the Pony Express was

founded, people admired the speed with which it delivered mail in the West. The

service gained a stellar reputation, often bordering on mythical. Perhaps that’s

why it shows up in numerous novels, even some set in times when the Pony

Express was no longer in business.

The Pony Express actually operated for

only eighteen months, from April 3, 1860 to October 26, 1861, although service

continued into November until all the mail in the agency’s possession on the

closure date had been delivered.

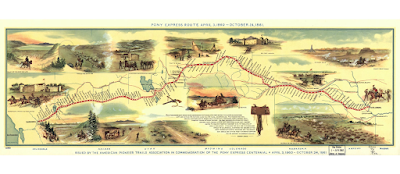

Before the telegraph and the transcontinental railroad, letters from the Midwest sent by stagecoach could take nearly a month to reach the west coast. If sent by ship, delivery could take several months. The Pony Express could carry mail from St. Joseph, Missouri to Sacramento, California in an average of ten days.

|

| Pony Express Route - Library of Congress |

In order to attain this speed of delivery,

the founders of this service—William Russell, Alexander Majors, and William B.

Waddell—established a series of nearly 200 stations, approximately ten miles

apart, across the current states of Missouri, Kansas, Nebraska, Colorado,

Wyoming, Utah, Nevada, and California. A rider generally changed horses at

every station along his 75-100 mile route to make sure the steeds were fresh

and could travel as fast as possible. Although the service was called “Pony”

Express, most of the mounts were actually horses. The preponderance of the

approximately 400 horses involved in the enterprise were half-breed mustangs

(referred to as “California horses”), Thoroughbreds and Morgans.

The main goal of the Pony Express was

speed, so great pains were taken to keep the weight the horses had to carry to

a minimum. Most riders were small, wiry and thin, weighing between 100 and 125

pounds. Their average age was about 20. Many teenagers, some as young as

fourteen, were employed. To further minimize weight, they wore close-fitting

clothes. It is unlikely that they wore wide-brimmed cowboy hats, even though

riders were frequently depicted with them. At any given time, a total of

approximately 80 riders could be on the route, including those going east and

those going west.

|

| This logo illustrates the special saddlebags. |

Special bags called mochilas were designed

to minimize weight and expedite horse and rider changes. The mochila had a

leather cover that fit over the saddle with four padlocked pockets beneath it.

The rider sat on the leather with a mail pouch on either side of each leg. This

special saddlebag could carry a total of twenty pounds, which was a significant

amount of mail since most of it was written on very thin paper.

Pony Express riders were required to swear

an oath to the company, in which they pledged in part: "I will, under no circumstances, use profane

language, that I will drink no intoxicating liquors, that I will not quarrel or

fight with any other employee of the firm, and that in every respect I will

conduct myself honestly, be faithful to my duties, and so direct all my acts as

to win the confidence of my employers, so help me God." Riders who broke

their oath risked being dismissed without pay.

Co-founder Alexander Majors gave each rider a leather-bound Bible and

asked that he keep it with him. Most likely, riders ignored him as the books

would have added weight thus compromising the effort to maximize speed.

|

| via Wikimedia Commons |

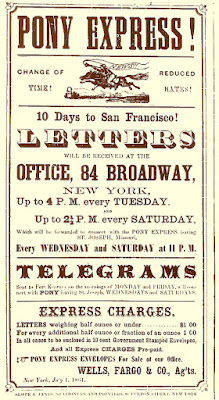

Sending a letter via the Pony Express was

an expensive proposition, another incentive for using thin paper. The company

initially charged $5.00 per half-ounce for each item sent. (That is more than

$130 in today’s money.) Even when the price was later reduced to $1.00 per

half-ounce, the cost was still too high for ordinary people to afford. Most of

the material transported by the riders was made up of government dispatches,

business documents and time-sensitive newspaper reports.

Despite the high prices they charged, the

Pony Express was a financial disaster. According to the Smithsonian Postal

Museum, the owners of the fastest mail carrying company in the country lost $30

for every letter they carried because they were not able to win a government mail

contract. They had lost approximately $200,000 by the time the service ended,

two days after Western Union completed the transcontinental telegraph line.

Buy Links: Paperback at Amazon Amazon print or digital