Several years ago, I wrote a blog about the challenge faced by historical fiction authors of using words that were common during the era when the story was set. (The word graphics are from that blog.) Since then, I’ve continued to struggle with my tendency to assume that a word is old when it turns out not to be. I’d like to share with you more of my discoveries.

When I was looking for a term to describe “a

small amount” to use in a story set in the late 1890’s two possibilities came

to mind – tad and dab. I looked them up and was surprised to learn that “tad”

as a small amount was not used until 1915, even though it had been previously

used to reference a small child. So “tad” was out for my story.

I had better luck with “dab.” Although the

noun was used to mean a “heavy blow with a weapon,” from around 1300, the

definition of a small lump or mass dates back to 1749. I could use “dab” in the

story.

In my book about the fight for women’s

suffrage, I wanted the protagonist to talk about the breakdown in the Senate

between supporters and opponents. But the term “breakdown” in the sense of such

an analysis did not show up until 1934. Consequently, I had to use more

cumbersome wording.

|

| Excerpt from the 12th Amendment |

The 12th Amendment first came into play in 1804, putting the presidential and vice-presidential candidates from the same political party on one ticket. However, the term “running mate” in the political sense did not come into play until 1888. Prior to that, the term running mate referred to a horse entered in a race to set the pace for a stablemate that had a better chance of winning.

A term that evolved in the opposite political direction is “executive.” The political use, as in the sense of the “executive” branch of government responsible to carry out and enforce the laws passed by the legislative branch, goes back to 1776. But the meaning relating to people in the upper echelon of a business hierarchy did not come into American usage until 1902.

|

| A car in the time before "beep" was a noun |

A big surprise was the use of “beep.” The

word derives from the sound of certain early automobile horns. Although

automobiles were numerous, especially in cities, in the first decade of the

1900s, the use of “beep” as a noun and a verb did not become common until 1929.

A similar tendency is to assume a

word is too new to use in my stories that take place around the turn of the 20th

century. One that pleasantly surprised me is “digs,” meaning the place where a

person lives or stays. I had always associated it with the beatnik and hippie

cultures of the mid-20th century. It turns out that the first use of

“digs” in this context dates back to 1893.

Lastly, when writing about the

1918 pandemic, I wanted to refer to a “bout of influenza.” The term “bout” has

been around with various meanings since the days of Middle English. However, “bout”

as a “term of illness” had not found its way into the common American

vernacular until 1939.

Have you ever been surprised by the origin of a word?

Buy Links: Paperback at Amazon Amazon print or digital

Really interesting, Ann!

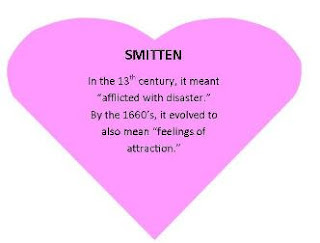

ReplyDeleteLove the change in meaning of the word smitten! (I suppose from smite, to strike.) Thanks so much for a fascinating article

Thanks, Lindsay. I run across these all the time when I'm writing.

DeleteI love etymology and the way language evolves. This is a. very timely reminder for all writers of historical books not to take even the most obvious terms for granted. Thanks, Ann.

ReplyDeleteThank you. Learning the history of words is part of the fun of looking them up.

DeleteWords, their use and how they've changed is endlessly fascinating. At the same time, writing historical for modern readers can also get a bit sticky. As time passes is gets more challenging and exciting to tell stories as authentically as possible using correct language. Still, I wouldn't change it for the world. Doris

ReplyDeleteMe neither. The words are part of the fun of writing historical fiction.

DeleteLoved this post, Ann, The history of words is fascinating. Like you, I've come to rely on my etymology dictionary. I love the word sassy but couldn't use it. Same with "teddy". I wanted my heroine to give Mike, the nickname Teddy Bear, but that phrase wasn't coined until well over a dozen years later, attributed to President Roosevelt, so I came up with honey bear. It's hard giving up a word that seems perfect but just not appropriate for the times. One can rationalize that for a word to become common usage, it was used much earlier, but one just can't risk upsetting a reader who really knows her history. Great post., I wanted to read more

ReplyDeleteThanks, Elizabeth. I keep a file of surprising word etymologies, which I refer to frequently and add to. One of my novels covered the period from from the 1890s to 1920. So I couldn't use 'suitcase' at the beginning of the story, but I could by the end.

ReplyDelete